Writers are often asked, “Where do you get your ideas?” Most of the time, we don’t really have an answer for that question. Sometimes, when you’ve been working on a book for more than two years, it even becomes difficult to remember where or how you got the idea for the book in the first place. I suppose for my current WIP (work in progress), I must have come across it in one of those many books of Florida history I had on my bookshelves in my old office on board our last boat, Möbius. So, after writing three big books that dealt with submarines in WW II, it seems my fascination with subs continues.

The interesting fact that fired up my imagination was that even before the United States entered World War II, Nazi U-boats had prowled the east coast and the Caribbean, sometimes as close as a couple of miles from shore. The American people were steadfastly isolationists at the time, and they did not want their country getting involved in the European War. However, that did not prevent Americans from sending supplies overseas, and the demand for those goods in the late 1930’s was helping Americans lift themselves out of the Depression. Once outside American waters, the German U-boats considered those tankers and cargo ships fair game, and American seamen were dying long before December 7, 1941.

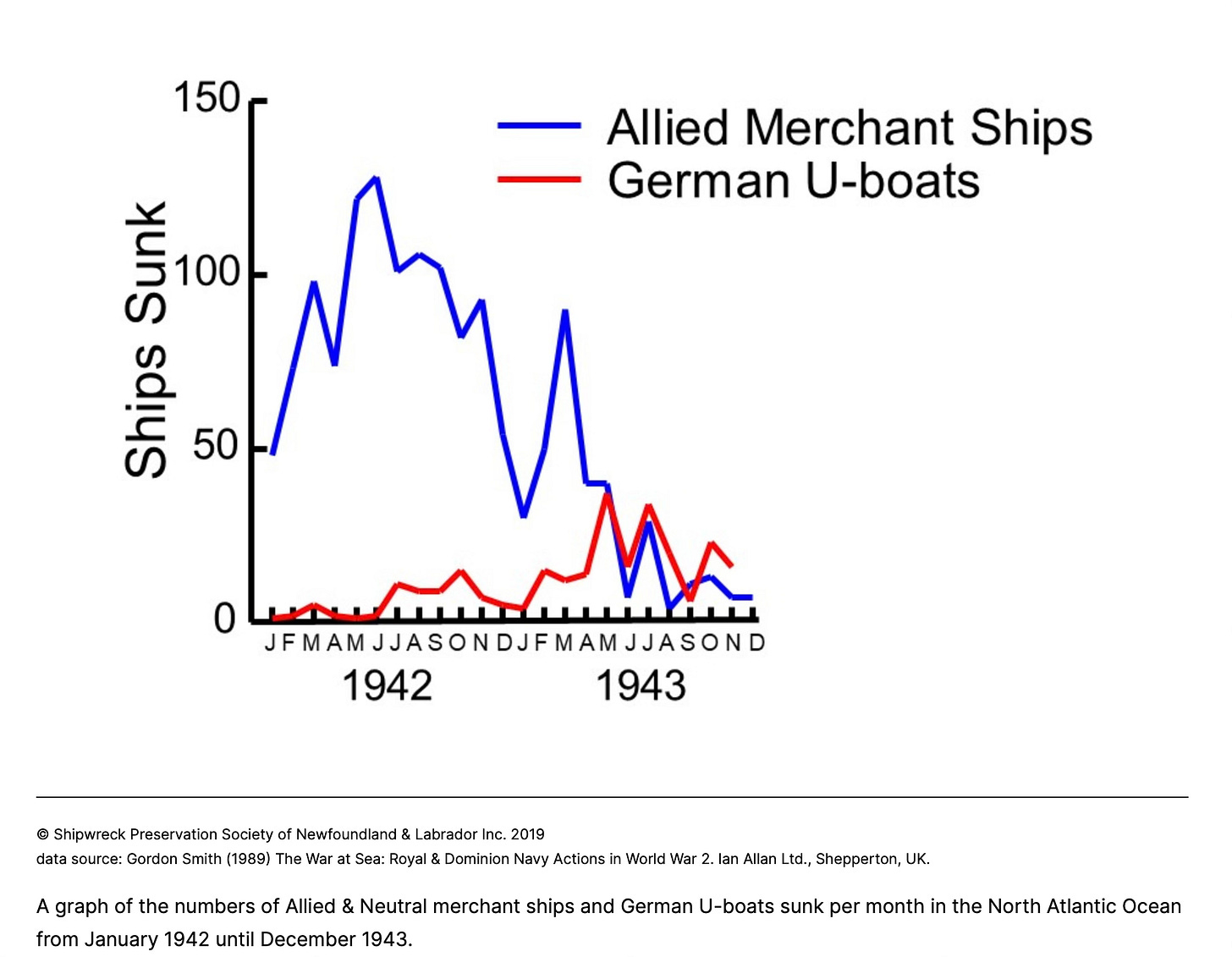

Once America entered the war, what was considered “fair game” changed, and we weren’t ready. The Nazis launched Operation Drumbeat sending 22 U-boats off on what they called “American hunting season.” Some historians have even gone so far as to suggest that the US military’s lack of preparedness nearly lost the war for the Allies in those first months after Pearl Harbor when so many desperately needed supplies were sent to the bottom of the ocean. We did not have the ships or planes to patrol and protect our waters from the battle-hardened German U-boats. American citizens still didn’t bother with blackout curtains, and the coastal lights silhouetted targets making it even easier for the U-boats to pick off their prey. In six months, nearly six hundred ships were sunk, most in American waters.

Of course, American shipyards were suddenly hard at work to rebuild our fleets, but ship aren’t built overnight, and the oil, gas and steel needed to build was aboard the cargo ships and tankers the U-boats stalked.

In those first months of 1942, seeing that America lacked the Navy or Coast Guard vessels to adequately patrol the coast, American civilian boat owners stepped forward and offered to fill the gap. From Maine to Miami, the owners of schooners, luggers, powerboats and fishing boats joined into flotillas to perform anti-submarine patrols. From Northeast’s fancy yacht clubs to the large shrimp fleets of the south, Americans assigned themselves patrols and were out working the waters to report sightings of U-boats, to tow in disabled vessels or lifeboats, and to pick up survivors in the water.

These boats were often painted gray and outfitted with old machine guns from the Spanish American War, or given hand deployed depth charges. Some were furnished with radios to report back to shore if they spotted a U-boat, or heard one at night when the subs had to come to the surface to run their diesel engines in order to charge their batteries. Sailing vessels were especially good for this because when under sail, unlike any other vessel, they could patrol silent and undetected.

These groups started up in various parts of the country on their own and gave themselves names. Eventually, the commodores of yacht clubs and the Cruising Club of America started to organize the sailors in the Northeast calling themselves the Corsair Fleet. Then the US Coast Guard got involved with creating the first iteration of the Coast Guard Auxiliary, referring to them as the Picket Patrol. But given the fact that most able-bodied young men were going off to war, many of these vessels were being crewed by a ragtag lot consisting of older seamen, men classified as "unfit for service," ex-rumrunners, fishermen, and other undisciplined ruffians. That’s why they were often called the Hooligan’s Navy.

In Florida, for obvious reasons, they nicknamed themselves the “Mosquito Fleet.” These stalwart sailors organized themselves as early as 1940 in ports like Jacksonville, Fort Lauderdale, and Tampa given that the state has 1,197 miles of coastline to protect.

On February 19, 1942, barely two months after Pearl Harbor, the cargo vessel Pan Massachusetts was sunk off Cape Canaveral. Three days later on the morning of February 22, the residents of Jupiter, Florida were awakened by a huge BANG when the tanker Republic was struck just offshore. The captain was able to run that ship aground before she sank. The following day, February 23, the tanker W.D. Andersen went up in a ball of fire in almost the same area off Jupiter. Only one man—who happened to be on deck and dove off when he saw the torpedo coming—survived. The war had arrived in Florida.

During the next year and a half as the Battle of the Atlantic raged on, Floridians often saw the smoke and flames of burning ships offshore. Tankers carrying oil from the Gulf had to pass through the narrow Florida Straits, and it was not uncommon for charred bodies to wash ashore on Florida’s white sand beaches.

Many of the yachts that became part of the Picket Patrol were famous race boats and giant motor yachts, and besides Hemingway, some notable crew included Humphrey Bogart and Arthur Fiedler.

One of my favorite stories about the Hooligan’s Navy concerns a Fort Lauderdale character by the name of Willard Lewis. I suspect the gentleman was quite the spinner of tales, as he supposedly had not one, but two encounters with U-boats. The first time, he was out on patrol in his own boat, the Diane, a 40-foot cruiser late one night off the Hillsboro Light when he and his crewman spotted the enemy vessel. He claims that he and his sole crew member looked at each other and shouted, “Let’s go!” and took off at full throttle charging straight at the surfaced U-boat. According to Coast Guard records, when “asked later what he hoped to accomplish by ramming a steel submarine with a wooden motorboat, Lewis explained, ‘I aimed at her conning tower . . . and I might have messed up something.’ The Diane missed the U-boat by about forty feet.”

Not long after that, Lewis became the hired captain of the Jay-Tee, a 40-foot cabin cruiser with a rebuilt Buick engine. Along with his crew member, a character named Uncle Bill (last name unknown), Lewis was out on patrol on May 6, 1942 searching for survivors from a tanker that had just been torpedoed, when they sighted a U-boat wallowing at the surface. Armed with a Colt 45 pistol, the Jay-Tee headed off in hot pursuit when the sub tried to dive, then porpoised back to the surface, then submerged again. Confused, Lewis began circling in the Jay-Tee. Suddenly, the men heard a loud crash and their boat was lifted several feet out of the water. Uncle Bill looked over the side and saw the steel deck of the Nazi U-boat that was surfacing beneath them. A few seconds later, the sub submerged.

Lewis and Uncle Bill returned to Fort Lauderdale with a story that was difficult to believe. But when the Jay-Tee was hauled out to check for damages, they discovered the wooden cruiser had a cracked keel and a streak of gray paint on her bottom.

In the end, there is no evidence of any of these Hooligans, nor of the civilian vessels that were commandeered by the Coast Guard and crewed with professionals, ever having succeeded in taking out a U-boat. Probably, more than anything it was a PR campaign, although the patrols did actually save the lives of many survivors from torpedoed ships.

For writers, stories like these are pure gold. The more I read about the Hooligan’s Navy, the more my imagination began to wander. Though they don’t get named in the history books, I am certain some were crewed by women, as women were filling men’s jobs across America. I began to imagine a young woman who had grown up in Florida sailing on her father’s old converted sponge schooner as he took our Northeasterners to fish the Gulf Stream. She heeds the call to take over as the boat’s skipper when her her father goes to work in Dooley’s Drydock building sub chasers, and her brother enlists in the Air Force.

So, that was where I got my book idea.

Fair winds!

Christine

Sources:

https://classicsailboats.org/the-coastal-picket-patrol-semper-paratus/

https://www.boatus.com/expert-advice/expert-advice-archive/2015/october/the-coastal-picket-force

https://wavetrain.net/2015/07/01/hooligan-navy-sailing-yachts-on-sub-patrol-during-wwii/

The Fighting Coast Guard: America's Maritime Guardians at War in the Twentieth Century. (2022). United States: University Press of Kansas.

U-Boats in New England: Submarine Patrols, Survivors and Saboteurs 1942-45. (2019). (n.p.): Fonthill Media.

Our vessel STEADFAST was part of this, patrolling Long Island and New Jersey with a gun on the bow!

May I link this story in one of mine? Such a great part of her history. Thanks for sharing! And researching!!

J

My mother grew up in West Palm Beach. She was not on the water, but rather above the water- in a two person plane! She was the spotter with binoculars. She says she never saw a submarine.